All compositions contain aspects of the creator’s thoughts and life at a particular time. Overundertone, a 2015 album consisting of eight electroacoustic tracks, is a reflection of me a decade ago. Listening to the album feels like reading an old diary. The me in 2015 is unfamiliar to the me in 2025 – he is passionate and curious about the world and people. He had the thoughts and emotions I wish to have now. Below are what I learn about myself when I listened to the tracks.

- Eyelid Spasm: I liked high frequencies, so I made a piece using them. I played with my (then) 5-year-old and 1-year-old sons, all the time, so the playfulness is in the piece. I even used a picture of me mimicking an animal (I think, I hope) for the kids as a cover photo. I don’t think I can hear many frequencies featured in this piece anymore.

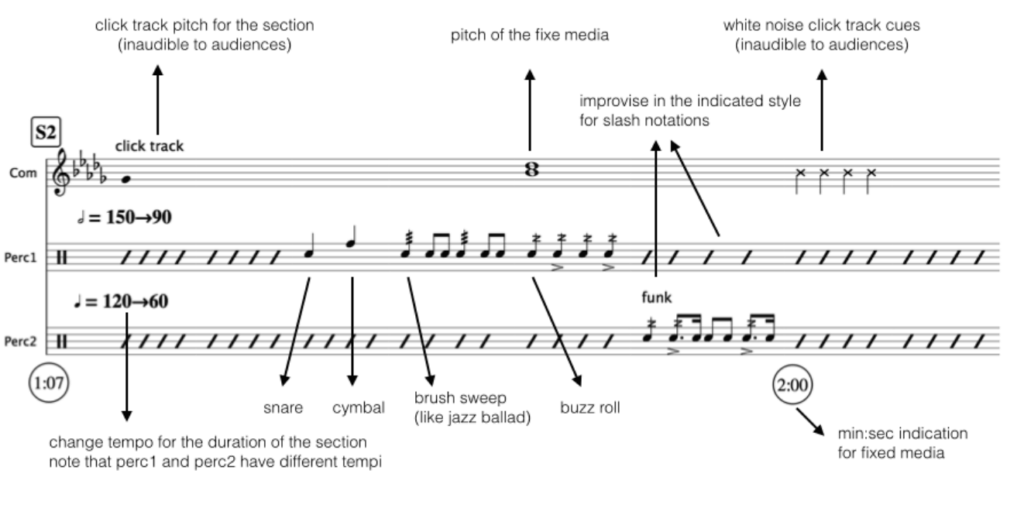

- Cross Rhythms: I wrote it as a class project example. I asked Oberlin’s TIMARA students to pick a page in Tom Johnson’s Imaginary Music and make an electroacoustic piece about it. I chose Cross Rhythms and composed a scene where two different rhythms overlap. The teacher-composer identity is in the piece.

- Three Corn Punch: It’s a recording of a live performance. It is probably my last piece that does not involve electronic sound. It uses a Disklavier, though. There are no new techniques here. I learned to accept that I don’t have to develop a new concept for every composition. A good idea from others and myself needs repetition, reinterpretation, and refinement.

- Cornfields and Cicadas: This is one of the soundscape works using original field recordings and synthesized sounds. I have been creating a series using this instrumentation since my graduate student years. I remember writing it with less struggle and stress, but the quality was about the same. It is a sonic diary of a vacation to a farm in Pennsylvania, where I went with my family and friends.

- Beft: I wrote it because I was a dad reading Dr. Seuss to the kids. Beft is a creature in Things You Can Think that only moves to the left. It contains sounds and techniques I loved then – Shepard tone, 8-channel spatialization, overtones, etc. It was also a part of a class project example, like Cross Rhythms. My teacher-composer-dad is all represented in Beft.

- Snake and Ox: It is a recording of an improvisation using instruments I used in solo shows. They are a no-input mixer, SuperCollider, and a custom synth. The no-input mixer sound was the most exciting thing to me. I remember dancing along with the no-input mixer noises while practicing.

- 10M to Fairmount: It is a sonic diary of a park in Philadelphia, where I lived for six years. Philly feels like a hometown since I started my family there. I must have been interested in visuals in addition to field recordings and synthesizers then. The piece has a video version. Like Cornfields and Cicadas, it is a diary-like piece.

- Sky Blue Waves: It’s a piece from 100 Strange Sounds, a project I thought would be my magnum opus. The track has a simple instrumentation (celesta and a field recording of a beach), but has the not-so-happy aspects of my life at that time. As a contrast to Eyelid Spasm, it worked well as a closing piece of the album.

These songs are forgotten, but are still significant to me. Overundertone is an archive of emotions, efforts, and life in audio, the format I love the most. The album reminds me to strive (용써라) like 2015. The jaded, slumped me of 2025 needs that.