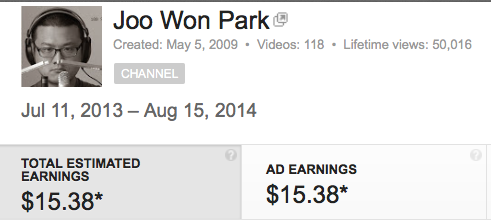

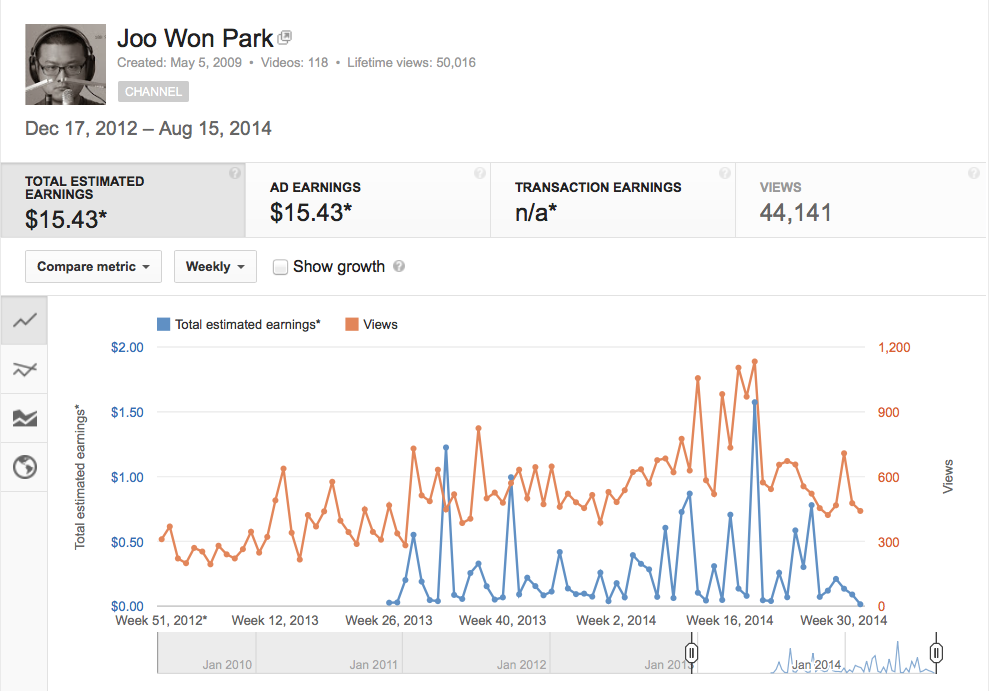

Self-assessment of solo set performances from 2011 to 2022

I analyzed instruments, gear, and repertoire of my solo electroacoustic sets from 2011 to 2022. For the sake of discussion, I categorize a set performance as a long-form performance (about 20 to 50 minutes) by artists without interruption or intermission. I find preparing, performing, and refining solo sets to be one of the best practices for live electronic music skills. In this article, I analyze the changes in hardware and repertoire in my solo electroacoustic performance by comparing video recordings of past shows. I hope the analysis serves the readers and me on what could be worth exploring in live electronic music.

Here are three video recordings of my solo sets as a point of reference.

- Indiana Electro-Music Group Performance (2013) https://youtu.be/UtuHB7Md1AQ

- Live from Studio B WOBC (2016) https://youtu.be/g877JGANZiM

- La Escucha Como Acción 08 (2020) https://youtu.be/B7aUFva0t8c

The videos represent my performance practices in three periods in three cities I worked and lived: Philadelphia (2009-2014), Oberlin (2014-2016), and Detroit (2016-current). The oldest solo set video I could find is from 2011 in Seoul, but the above videos are unabridged and have direct outs from the house mixer.

Performance Preparation

Practicality and flexibility matter in a set performance. Venues have sound systems with varying designs, and sharing the stage with other artists doing a set is common. Therefore, I choose pieces according to the external limitations I cannot control. My gear is compact and travel-friendly to set up and strike quickly, regardless of the venue’s PA capacity. I plan 15 minutes or less to set up, get ready to go on stage, and carry an extra direct box and cables.

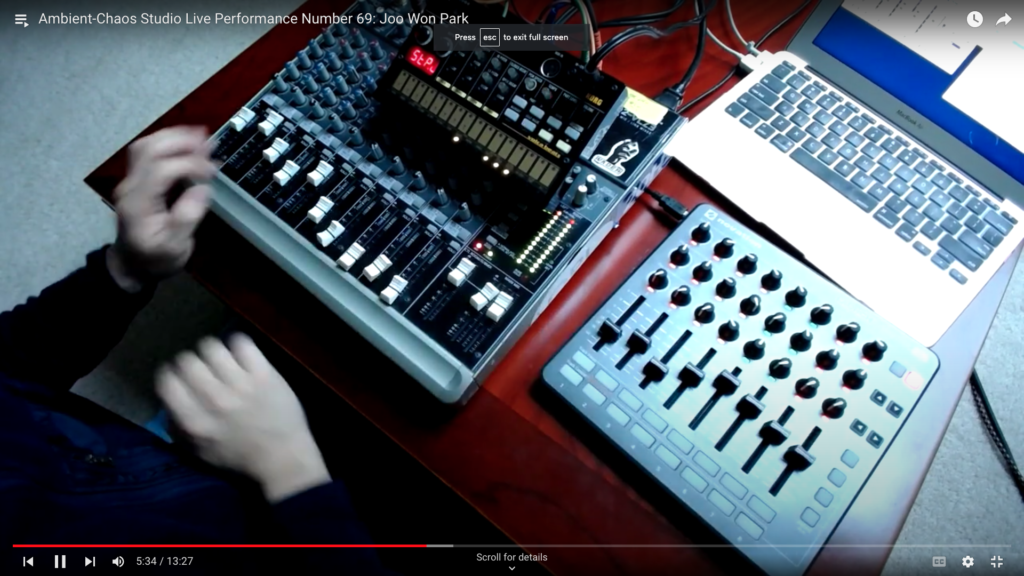

The most efficient setup could be solo laptop performance. But I am not inclined to present in that format as the audience cannot see movements behind the computer screen. The gear placement reinforces the visual cues in my shows. I value establishing a connection between what I do on stage and what the audience hears. In the reference videos above, the laptop is on the right side of the table. Most sound-generating objects and body actions are in the center and have an unobstructed view. When possible, I place the front panel of electronic instruments observable to the audience. For example, the picture below is my setup in October 2022. I put the gear on a piano bench for the audience to see the fingers moving across the buttons and sliders. The laptop created sound, but it was tucked below the bench. I launched the SuperCollider patch before the show and did not need to touch or look at it when performing. Not shown well in the picture is a small three-channel mixer on the floor. Like the laptop, there was no need to touch the mixer after the sound check, and it did not need to be on the table along with the instruments.

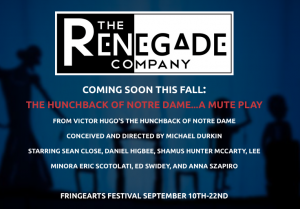

The 2013 Set

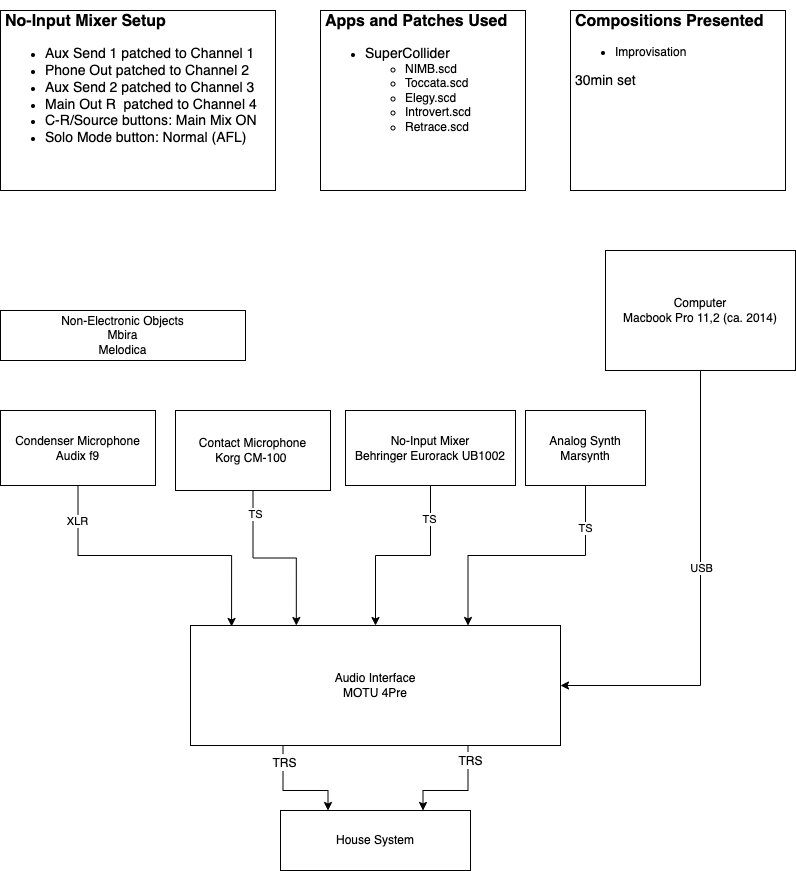

The diagram below depicts the connection of the hardware used in the set. The three boxes in the diagram contain the no-input mixer patching method, a list of SuperCollider patches, and compositions incorporated in the set. SuperCollider is the sole software I have used in solo performances since the early 2000s. No-input mixer patching details differ from artist to artist, and it is worth documenting my preferred patching for comparison. I will use the diagram in the same format for the 2016 and 2020 sets.

Hardware choices depend on the repertoire. The title track of the performances in 2013 was Toccata, an improvisational piece featuring a wooden board, various acoustic objects, and a live processing SuperCollider patch. A combination of a contact microphone and a small diaphragm condenser mic captured sent audio signals in the air and the board. The condenser mic doubled as an audio input for other pieces like Retrace, Introvert, and Elegy. Retrace is my first SuperCollider composition incorporating an acoustic instrument. The solo set format allowed me the repeated performance of Retrace and gave me multiple chances to refine it. The picture below, taken at a 2013 Indeterminacies series in Tennessee, is an example of a typical performance layout.

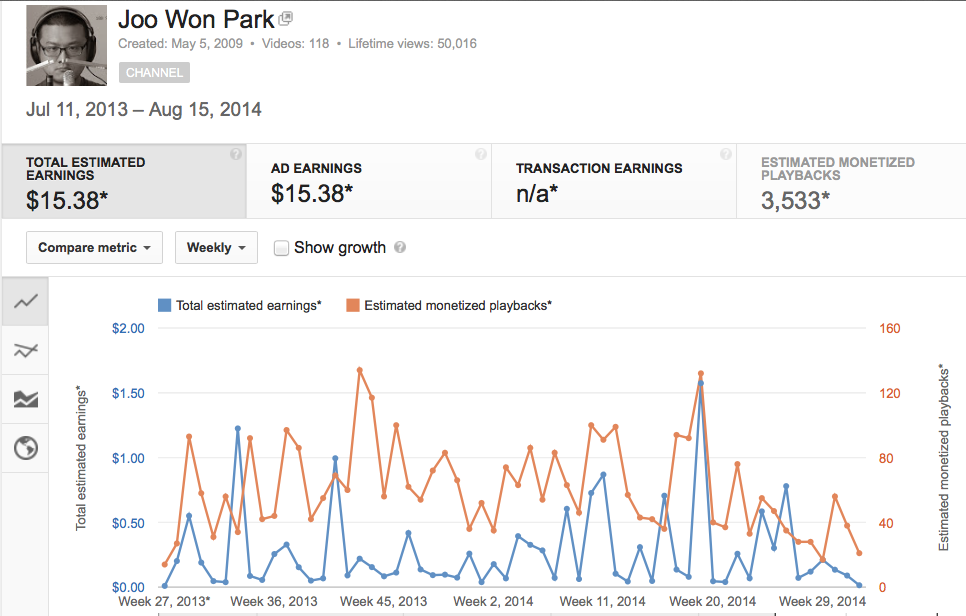

The microphones were connected to an audio interface with four inputs and outputs. Audio inputs 3 and 4 allowed me to connect outputs from a no-input mixer. In 2013, the sounds of the no-input mixer and the synths took up a small portion of the show. I used them for the first time to create videos for the 100 Strange Sounds project and was not proficient in performing them. From 2013-14, many objects I experimented with in 100 Strange Sounds became part of Toccata. It refined the piece composed in 2009 for four or more years.

Video projection was also part of a performance in 2013. Both Introvert and Elegy have accompanying videos, and I often used the laptop’s built-in camera to project the hand movement on the wooden board. The 2015 performance at New Music Gathering is an example of such a set. The on-stage live video reinforces the connection between what I do and what the audience hears, but not all venues can accommodate large-screen projection systems. Setting up a proper video meant extra tech time, a possible nuisance for tech people and other artists on the same show. The reduction in practicality led me to retire the video features from the set gradually.

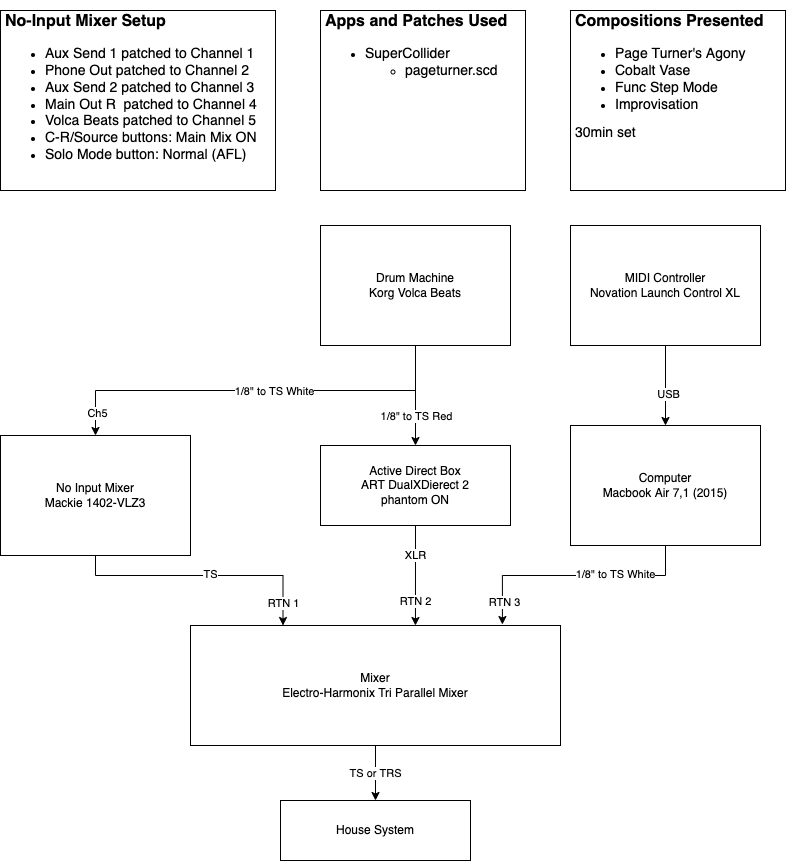

The 2016 Set

I avoid unintentional silences between the pieces in a set performance. In 2013, I often played pre-recorded sounds while adjusting SuperCollider patches for the next piece. In 2016, all transitions became superpositions of the end of a piece and the beginning of the next one. The crossfade time got longer and smoother with more experience, blending multiple works. This approach stimulated new compositions combining two or more previously featured instruments. Consequently, my set became a single long-form improvisation featuring all the instruments I could carry comfortably. The 2016 WOBC video recording serves as an example.

Out-of-town gigs outnumbered in-town opportunities when I lived in Oberlin. Traveling with a carry-on bag full of gear became burdensome, and thus I sought to develop a set with as few instruments as possible without degrading the quality. In 2015, I had an opportunity to perform on a double-decker tour bus. The setup time was short, and the performance space was small due to the particular nature of the gig. So I chose to abandon the laptop, the instrument I am most skilled at, and performed with a no-input mixer and a monophonic synthesizer. The success and fun I had in the gig encouraged me to add more non-computer elements to the set.

The 2020 Set

By 2016, I felt at home performing with a contact mic and found objects. But doing so felt less exciting and challenging. In contrast, my interest in drum machines and MIDI controllers grew. The resulting pieces were Cobalt Vase and Page Turner’s Agony. By combining Cobalt Vase with no-input mixing, I composed Func Step Mode. These three pieces are currently the main ingredients of my solo set of electronics-only improvisation. The video made for La Escucha Como Acción’s COVID online performance series is an example.

The current set does not include visually expressive works like Toccata. Microphones and found objects are absent, limiting sonic and visual possibilities. But I gained mobility and a chance to showcase my skills on specific instruments in return. The set sends mono output and can work without an audio interface. The output choice is efficient but could be risky in a genre that values high-fidelity and multi-channel audio. But I identify the most with the sound of the current set.

Findings from Analysis

Reviewing a decade of set performances was an opportunity to evaluate what I value most in live electroacoustic music. I value practicality and refinement. I accept that practicality gets priority over aesthetics in my music. Some pieces are no longer in the setlist because they involve more physical labor and are prone to technical errors. The longest surviving instrument over a decade, besides SuperCollider, is a no-input mixer: it takes a short time to set up and is immune to software updates. This reliability led to more time spent with the mixer. A deliberate decision on one instrument is worth noting in technology-based performance, in which one can access an uncountable number of synthesizers and controllers. Currently, I feel proficient at performing a no-input mixer. I am developing a similar feeling toward Korg Volca Beats. Efficiency affects aesthetic choices in my music.

I recommend designing, executing, and revising a solo set for electronic musicians. Preparing and practicing sets builds muscle memory and opportunities to overcome weaknesses. Compositions featured in a set get continuously refined with repeated performances. Combining and remixing works in a set often inspires new compositions. The refining process is a luxury for compositions written for others, but set performances demand it by nature.