Mark Applebaum’s Aphasia (2009) for solo performer is a difficult but rewarding piece. I have been intermittently practicing it since 2021, but I have yet to reach a satisfactory level. Knowing that my run of the piece today is better than in any other day, it gives me joy and energy to keep practicing. I wanted to share that delight in the last month’s Wayne State Faculty Recital Series. Despite many mistakes, the performance was received well by students and guests. Aphasia attracts and affects audiences and performers like no other electronic pieces I know. I can think of two, perhaps very personal, reasons.

Soulslike

Aphasia is an Elden Ring-equivalent of electroacoustic music. The unforgiving difficulty is part of the fun. In practicing Aphasia, I had innumerable “YOU DIED” moments. Learning small sections required focus and discipline, and still, the chance of succeeding was slim. But like a soulslike game, the process of achieving goals was fun. I understood more about the piece’s structural relationships, sound design techniques, and choreographic thoughts through repeated readings, listening, and failing.

When I memorized the piece, I felt joy, similar to the moment I beat the final boss in Elden Ring after hundreds of hours of playtime. I learned to work consistently to achieve seemingly impossible goals. Musicians, of course, acquire this trait, but I needed a reminder and reinforcement. Practicing Aphasia during the COVID quarantine semesters did that job.

The audience watching Aphasia immediately gets its pleasant-but-difficult aspect. It’s fun but serious. It’s confusing, but there’s the order. And it’s inviting – instead of “I can’t do what I see on stage,” the audience may feel “I want to try it one day.” Aphasia seems to be an excellent introduction to studying the performance aspect of electronic music. Once a person has experience of doing Aphasia, watching the performance has a new meaning. It’s like watching a PVP match when knowing the mechanics and insights of a video game.

Notation

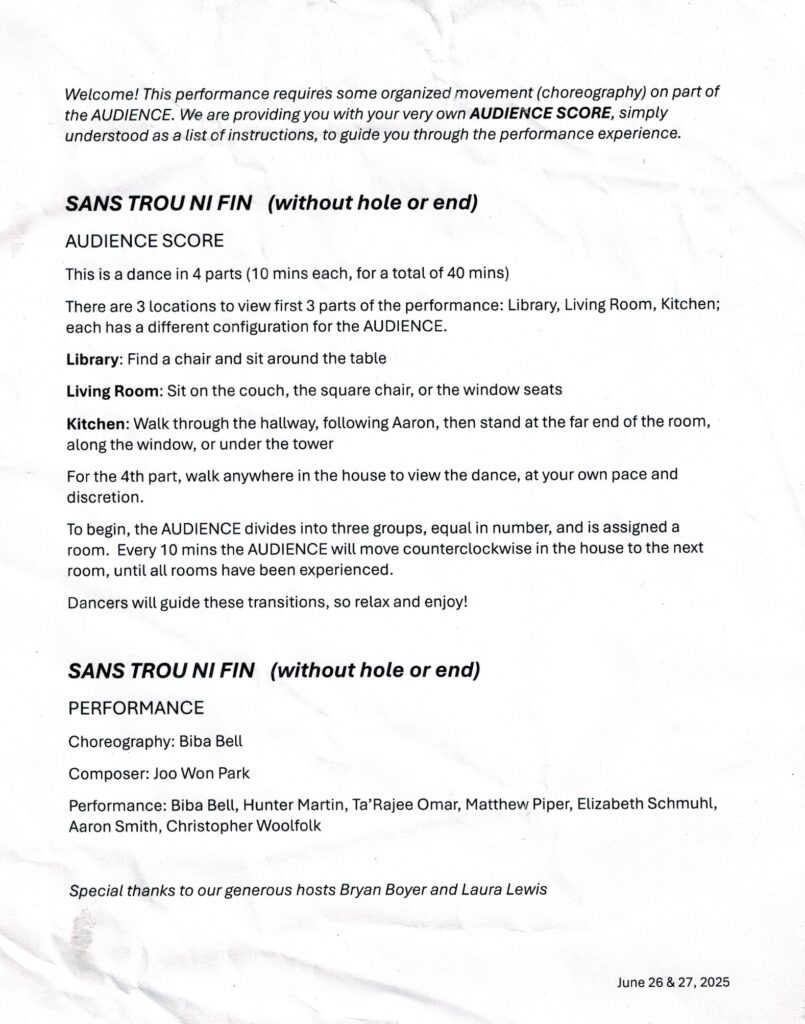

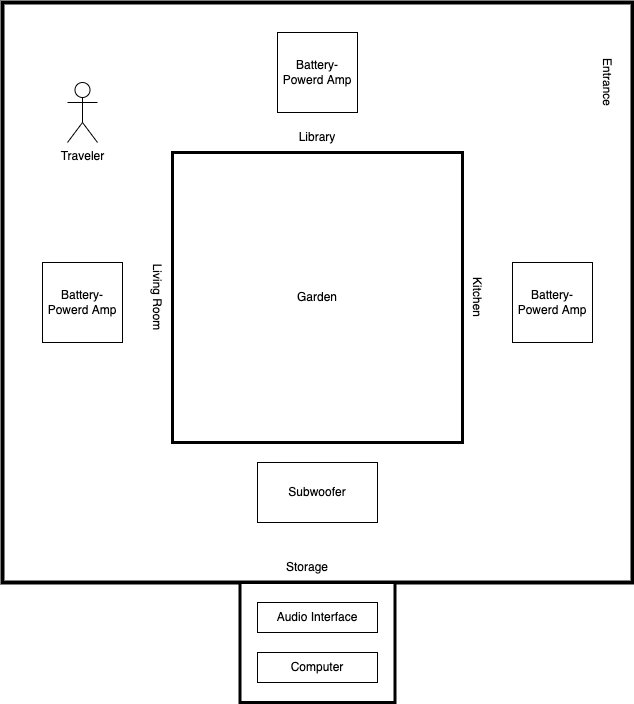

Aphasia is a fully-notated piece composed in 2009. Hundreds of performers, mainly percussionists, played it in the 2010s. In contrast to many graphic notations, the score is not to be freely interpreted. There is a clear notion of a mistake when the performer misses the timing or makes a wrong hand gesture. This aesthetics contrasts with my solo performance practice in the 2010’s, in which I freely improvised on stage with found objects, MIDI controllers, and found objects. The improvisatory nature of my performance made the audience expect the unexpected at the expense of irreplicability – I was the only person who could perform my solo electroacoustic works. In the composer of Aphasia’s words, I was the best and the worst performer of my piece.

While only the improviser could perform their pieces, hundreds of percussionists performed Aphasia as the composer intended. Aphasia’s technology barrier is low, and the piece is a hit in every concert. When done correctly, the piece is indistinguishable from many high-tech compositions using motion sensors or controllers. Performers can make such an experience by studying notation, like many other pieces that they have studied previously.

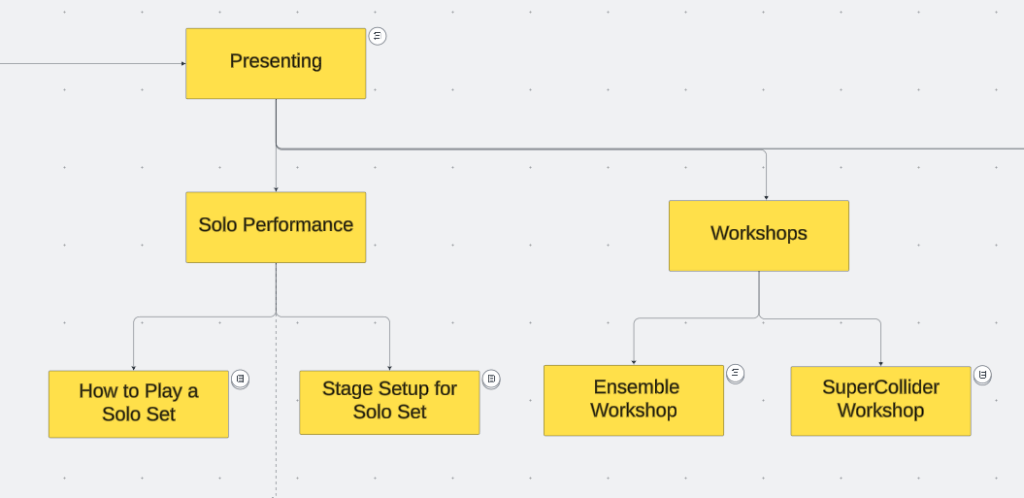

Aphasia taught me the effectiveness of low technology and low dependence on improvisational skill. With well-written notation, such a composition travels far, invites more performers, and lasts long. Many mixed pieces (i.e., those with an instrument and prerecorded electronics) have the same strength, but Aphasia stands out by featuring the most accessible instrument. My recent electronic ensemble pieces reflect this approach. They are built to be transferable, non-virtuostic, and have low technological/financial barriers.

Summary

Aphasia reinforces the music fundamentals I often forget – practicing and overcoming challenges is an essential part of musicianship, and great notation makes performers change and improve. I forgot these, perhaps as a byproduct of pursuing the new and the cutting-edge as a profession.

Learning Aphasia also rekindled my role as a student. To create and teach, I need to study and practice. Consistently and continuously. The result of doing so does not have to be perfect, but sharing and explaining what I experienced is what teacher-artists do. Knowing me, I will probably forget the lessons. When that happens, I will relearn Aphasia (and/or play Elden Ring) to remember it again.