In Four Hit Combo, each laptop ensemble member uses four audio files to create twenty-six flavors. Musical patterns arise from repetitions (loops), and different combinations mark forms in music. The laptop ensemble members prepare their own samples before the performance, and they control loop start points and duration according to the score and the conductor’s cue. Because there are no specific audio files attached to the piece, each performance could give a unique sonic experience.

Instrument Needed

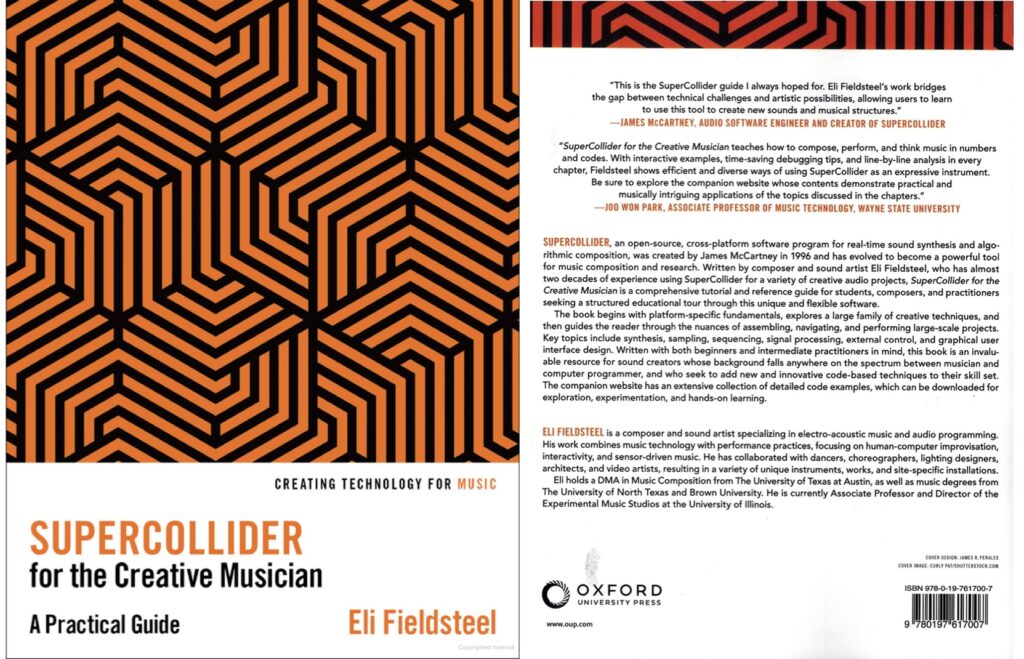

- Laptop: each performer needs a computer with SuperCollider installed

- Amp: connect the laptop to a sound reinforcement system. If the performance space is small, it is possible to use the laptop’s built-in speaker.

Pre-Performance Preparation

- Determine a conductor and at least three performers. If there are more than three performers, parts can be doubled

- Each performer prepares three audio files (wav, aif, or mp3). The first file should contain a voice. The second file should contain a pitched instrument sound. The third file should contain a percussion sound. All files should not be too short (less than a second) or too long (more than a minute). The [voice], [instrument], and [percussion] files should be different for all performers.

- While the voice, instrument, and percussion files are different for all performers, they should share one common sound file. This file will be used in the [finale].

- The conductor prepares one audio about 10-30 seconds long. It could be any sound with noticeable changes. For example, a musical passage would work well, while an unchanged white noise would not.

- Download FourHitCombo_Score.pdf, FourHitCombo_Performer.scd, and FourHitCombo_Conductor.scd from www.joowonpark.net/fourhitcombo

- Open the .scd files in SuperCollider. Follow the instructions on the.scd file to load the GUI screen.

Score Interpretation

- Proceed to the next measure only at the conductor’s cue. The conductor should give a cue to move on to the next measure every 10-20 seconds.

- In [voice], [instrument], [percussion], and [finale] rectangle, the performers drag-and-drop the audio file accordingly.

- In [random] square, performers press the random button in the GUI.

- In the square with a dot, quickly move the cursor in the 2D slider to the notated location.

- In the square with a dot and arrow, slowly move the cursor from the beginning point to the end point of the arrow. It is OK to finish moving the cursor before the conductor’s cue.

- In a measure with no symbol, leave the sound as is. Do not silence the sound.

- In measure 27, all performers freely improvise. Use any sounds except the commonly shared sound reserved for [finale].