Seokseok Bell is a track in Dot Zip, an album of 22 generative music. The album’s purpose is to demo a uniquely electronic sound rendered with codes. Each track has a downloadable SuperCollider code that a listener can render and modify. Listen to SeoSeok Bell at Bandcamp and download the SuperCollider code from here.

The following paragraphs analyze the form, code, and musical aspirations in making Seokseok Bell. It teaches how to start and progress a composition from a single synthesized sound. The learning is most effective if the reader has a SuperCollider installed on their computer. Please watch a tutorial video on how to run SuperCollider codes written for Dot Zip.

Program

Seoseok (서석) is a small town in the mountainous region of Korea. The sound of the bell in a chapel in the town reminds me of peace and love. The piece recreates (or interprets) the bell sound using an additive synthesis-like process and then presents it in an ambient-like style.

Form

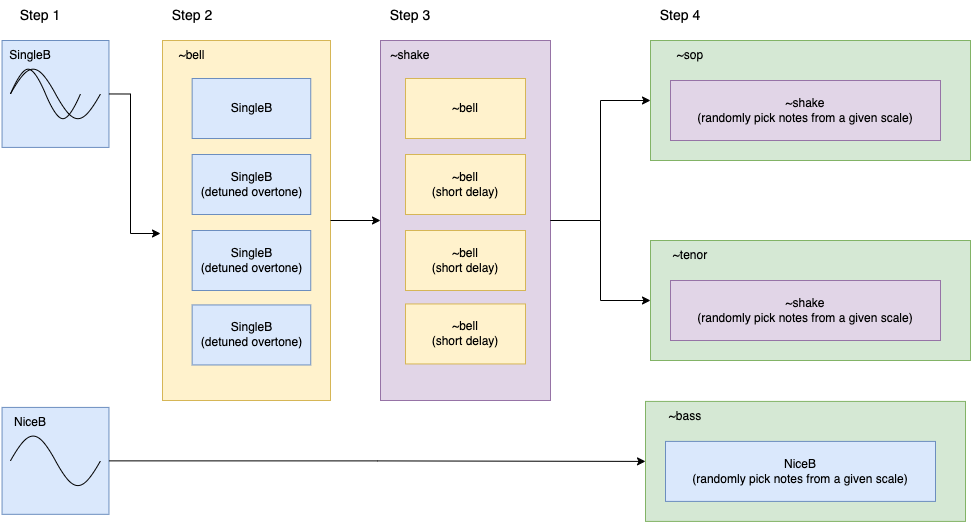

Seoseok Bell creates a bell-like tone by adding multiple sine waves. The bell tones and a simple bass line then make a three-part contrapuntal music. The resulting music has many variations due to the randomization in overtone frequencies, note sequence, and rhythms. The SuperCollider code SeoSeokBell_DotZip.scd does this through the following steps.

- Step 1: Make two sine waves detuned to each other with a randomized frequency difference, creating a single tone with a pulse.

- Step 2: Create an overtone series. The notes in the overtone series are randomly detuned.

- Step 3: Play the sound multiple times with short, randomized time intervals.

- Step 4: Generate soprano and tenor parts by randomly choosing a note in a scale. At the same time, generate a bass part with simpler overtones in tune.

Code

SeoSeokBell_DotZip.scd has the following sections. Watch a tutorial video on how to use the code.

- SynthDef(“SingleB”): synthesizes sound described in Step 1

- ~bell: makes sound described in Step 2

- ~shake: make sound described in Step 3

- ~sop, ~tenor, and ~bass: make sound described in Step 4

- SynthDef(“NiceB”): synthesizes bass tone described in Step4

- SystemClock.sched: schedules start and stop time of ~sop, ~tenor, and ~bass

SynthDef(“SingleB”) and SynthDef(“NiceB”)

The two SynthDefs use simple waveform generators (SinOsc.ar and LFPulse.ar) as audio sources. SynthDef(“SingleB”) uses a percussive amplitude envelope with randomized attack and release times. The envelope also includes a transient generated with LFNoise2.ar. The SynthDef(“NiceB”) has an envelope on the filter frequency of RLPF.ar.

~bell

In ~bell function, SynthDef(“SingleB”) is duplicated using Routine. The below formulas determine the frequencies of the duplicated Synths.

pitch=(freq*(count))*rrand(0.99,1.01);pitch2 =pitch*(interval.midiratio)*rrand(0.99,1.02)*rrand(0.99,1.02);Where argument count is increasing by 1 at every iteration of a .do loop

Once defined, ~bell function generates a sound using the following arguments:

~bell.(fumdamental frequency, amplitude, duration, pan position, interval value of overtones)~shake

~shake duplicates function ~bell with a Routine with randomized .wait, creating a slight delay between the instances of Synths. Once defined, the ~shake function generates a sound using the following artumdnts:

~shake.(fumdamental frequency, amplitude, duration, interval value of overtones, delay time)~sop, ~tenor, and ~bass

The three functions ~sop, ~tenor, and ~bass are Routines that play ~shake or Synth(“NiceB”) with frequencies picked from the array ~scale or ~scalebass. The global variables ~bpm and ~beat determine the wait time. The three Routines receive .play and .stop messages according to the timings set by SystemClock.sched.

Uniquely Electronic

In electronic music, a sound design process is often the starting point of a composition. Seoseok Bell began as an exercise inspired by the Risset Bell. I wanted to create a bell sound using additive synthesis. However, such an exercise should not end as a sound design only. The composer or researcher should present the findings in a musical context.

More Analysis and Tutorials

- 847 Twins – Brief Analysis: analysis of a piece in the same format as the above

- End Credits – Brief Analysis: analysis of a piece in the same format as the above

- Computer Music Practice Examples (CMPE) – tutorials on using computer music technology for instrument design, composition, performance, and presentation