Joo Won Park

For Promotion and Tenure Application (2021)

A music technologist is a composer, performer, and instrument maker whose primary tool is electronic devices. I am a music technologist specializing in electroacoustic composition, solo performance, and electronic ensemble. As a teaching musician, I share ideas of uniquely electronic sounds and performance practices with my students. Over one hundred presentations of my work in the past five years prove my contribution and significance in the field.

I strive to be prolific, consistent, and strategic in my creative process to be a better scholar with a distinct sound. A highlight of my research outputs since my hire at Wayne State University in 2016 includes:

- 2 full-length solo albums

- 3 peer-reviewed albums

- 3 collaborative albums

- 18 performed and recorded electroacoustic compositions in solo or ensemble format

- 1 peer-reviewed article on music technology at an international-level journal

- 2 articles for a local music agency and the College Music Society

- 5 electronic music apps

A summary of publications, presentations, grants, and awards since 2016 proves that my research is a significant contribution to the field of electroacoustic music:

- Presented electroacoustic compositions at 34 peer-reviewed conferences and festivals

- Received 38 invitations to present electroacoustic compositions at national and regional events

- Presented 19 shows as a featured solo artist or ensemble director

- 21 different electronic ensembles performed my pieces nationwide

- 26 paper presentations and guest artist talks

- Produced 12 campus electronic music concerts

- Received 4 grants or awards: High Wire Lab Award ($1000, external), Arts and Research Humanity Research Support Program ($5500, internal), New Music USA Grant ($2970, external), and Knight Arts Challenge Grant ($5000, external)

- Received 2020 Kresge Artist Fellowship ($25,000)

A list of professional services shows the electroacoustic community’s trust in my experience and expertise.

- Society for Electroacoustic Music in the United States: board member since 2016

- Korean Electroacoustic Music Society’s Conference: editorial member since 2013

- Associate Director of Third Practice Electroacoustic Music Festival since 2009

- Juror in 19 national and international peer-reviewed conferences and journals

As electroacoustic music may be an unfamiliar topic, I pay extra attention to guide the audience through my creative and aesthetic choices. In addition, reviews of my work in the media highlight my creative process. Below is an excerpt from my interview with Cleveland Classical in 2019.

“It’s one thing to push yourself out of your comfort zone. It’s quite another to deliberately put yourself in risky situations over and over again — part of the artistic strategy of electroacoustic composer and improviser Joo Won Park. “I like to solve a puzzle in front of the audience,” he said during a telephone conversation from Detroit.” [H-12]

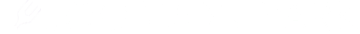

The puzzle I solve involves technology. I create and apply technology to extend artists’ ability to produce sound beyond human capacity. All my works feature what machines can do uniquely or better than humans. Touch [M-1] is a work I perform most often in tours and solo concerts. It is a culminating work that stemmed from 100 Strange Sounds (www.100strangesounds.com), a YouTube project of one hundred solo improvisations featuring everyday objects and electronics. In my interview with Paolo Yumol for Killscreen.com, he articulated the goal of the project, writing:

“In many ways, 100 Strange Sounds captures the spirit of Park’s work as a whole; it demonstrates the lengths to which Park will go to find the musicality in his everyday surroundings, to find the beauty in mundanity. Park sources ideas from his immediate surroundings and day-to-day experiences, whether it be spending time playing with his kids or walking around Detroit.” [H-15]

Touch and 100 Strange Sounds have positive elements I continue to cultivate in other works. They also taught me a limit I had to overcome. My pieces before 2016 used specific, expensive, and difficult-to-operate software and hardware. These instruments ensure high audio quality and performance capability, but few performers can replicate or present the piece without my assistance. Addressing technical affordability and replicability while maintaining satisfying artistic quality is my ongoing mission, and I approach it by starting a composition with instrument design.

I code free and original software synthesizers and performance systems that run on multi-platform computers. Doing so lowers the technological and financial barrier for performers who wish to present my pieces. I also choose to use cheap and readily available hardware and build a simple interface to minimize a technical expert’s involvement. As one can hear in Hungry [M-1], taking out everything except the essence is more than a presentation method. It is an aesthetic goal I follow. Mo Willems said, “simple and easy are opposites” In his drawing tutorials for children, and I wholeheartedly agree with it.

Like Willems’ picture books, I want the audience and the performers to be delighted when they experience my music. If listeners and performers feel unexpected joy by discovering a musical relationship between humans and machines, they understand my intention. In PS Quartet No.1, [M-1], ensemble members use their decade(s) of video game muscle memory to make music with game controllers. At the end of Beat Matching [M-1], I ask performers to shape their mouths as if they were making funny sounds while brushing their teeth. When these human actions interact with a custom application I created, the ensemble engages in a uniquely electronic sonic experience. These sounds are also guaranteed to be different at each performance by design.

I aim to craft these unrecordable moments in electroacoustic music. As a director of the Electronic Music Ensemble of Wayne State (EMEWS), I share this goal with a talented group of students. EMEWS is an all-undergraduate electronic music ensemble consisting of current Wayne State Warriors. EMEWS won the 2019 New Music USA Grant to do a week-long East Coast tour [II-C4]. I am confident that the group, which was as large as 22 students in Winter 2019, is one of the most performed and traveled undergraduate electronic music ensembles in the nation before the pandemic.

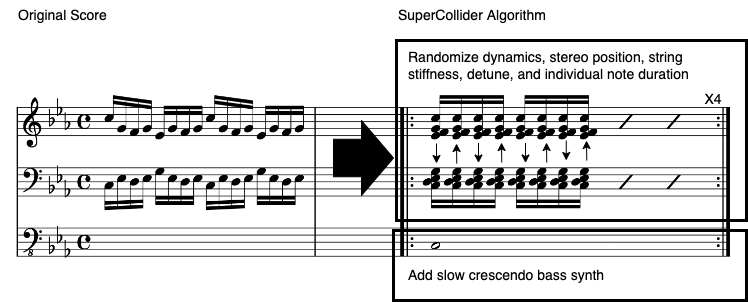

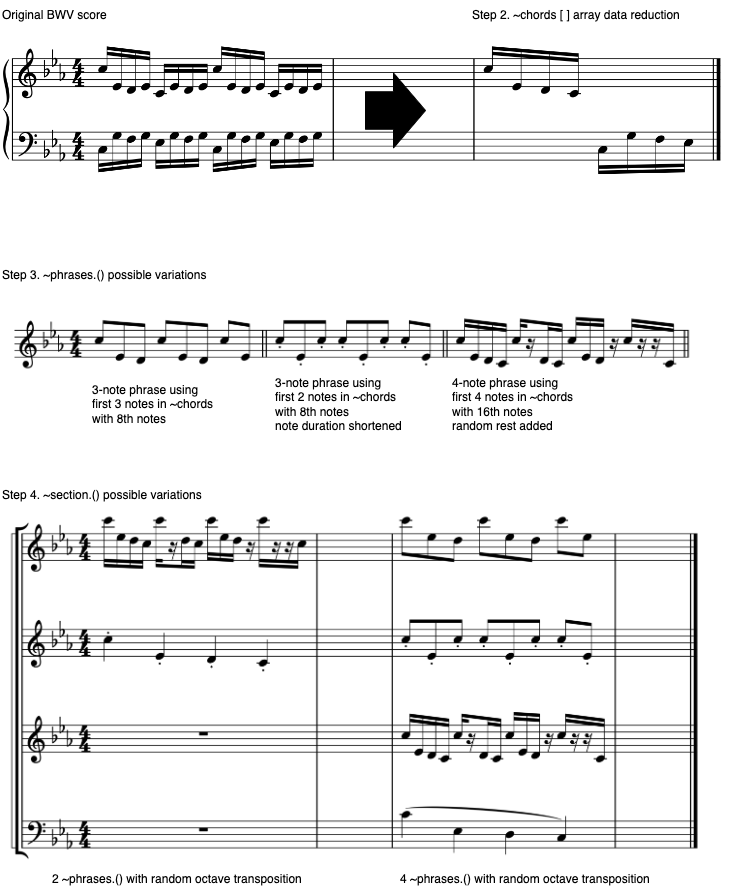

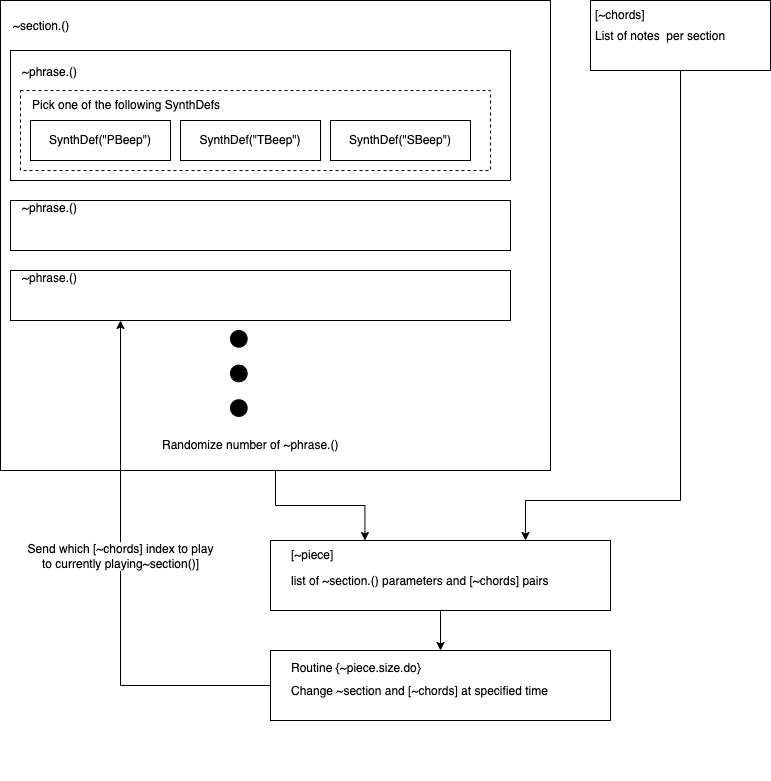

In 2018, I received the Arts and Humanities Research Support grant to further research electronic music ensemble performances. The grant allowed me to compose and present EMEWS pieces that are uniquely electronic and transferrable. Twenty other electronic ensembles that performed my pieces show I achieved my goal. Among those ensembles, eighteen rehearsed my pieces without my involvement. As a closure to the Arts and Humanities project, I published an article about ensemble instrument design in a peer-reviewed journal [III-D2].

When institutions invite me for guest lectures and presentations, I highlight the importance of improving electronic music craftsmanship. One method I recommend is choosing one or two electronic instruments to practice consistently and explore all possibilities. For example, Cobalt Vase and Func Step Mode [M-1] are pieces for a drum machine that I have practiced for a few years. The instrument needed for these pieces is readily available, but the performance techniques I explore are not. To teach and document the methods, I developed a graphical notation for the drum machine. Seven Bird Watchers [M-1] uses such notation, and the ensemble members can now create sounds that took me a year to develop in one rehearsal.

The COVID-19 followed shortly after the recording of Seven Bird Watchers. I feared that my research focus on the here-and-nowness of electroacoustic music might need to pause. However, I learned that I could share my research without compromise by rethinking the presentation method. Computer Music Practice Examples (CMPE) [M-1] is a series consisting of apps, streaming videos, codes, and tutorials. The participants download a free application to make music and learn about its production process by watching original videos and slides. Bypassing streaming audio and excluding expert performers, CMPE users experience what I hear in my studio with a few mouse clicks. Additionally, they have permission to use or modify the apps for their artistic practice.

Computer Music Practice Examples is a continuation of my goal to create and present a uniquely electronic, unrecordable, and delightful experience. The project may not have a chance to be evaluated by peers before the tenure review, but below Facebook data proves its potential and influence.

- ~16500 total views (5/16/20-7/25/21)

- 945 followers (as of 7/25/21)

I am confident that I became a better researcher, musician, teacher, and community leader over the past years working at Wayne State University. The extra challenge in 2020-2021 made me even more ready to tackle projects requiring long-term commitment and institutional support. When tenured, I plan to mature the relationship I built with the Detroit music community through continuing involvement. I also have a vision to create more significant interdisciplinary projects. A committed partnership with the city and the state, combined with the Music Technology program’s steadily growing alumni, will attract new undergraduate applicants. They will become a regional and national musical force when they graduate. I will refine and enhance this virtuous cycle by continuing to be a creative role model.

Another post-tenure goal is to share my expertise with the broader community by increasing the number of presentations and publications at international-level conferences. As for teaching, I want to position Wayne State’s Music Technology program as the leader in Michigan and beyond. I want to devise a plan to attract more out-of-state and international students, working professionals, and established artists. This progress will be parallel to the constant update and improvement of the current curriculum.

The included tenure and promotion packet provides details on my steady growth as a music technologist. The document also proves my long-term and continuing commitment to creative research, teaching, and service. For the most recent updates, please visit my website www.joowonpark.net.